In Shakespeare’s comedy As You Like It, the woeful Jacques wanders the Arden Forest spoiling the merriment of his compatriots.

Serving as foil for the otherwise raucous revelry, Jacques is described by one character as “the prince of philosophical idlers.” And though this despondent dawdler is not among Shakespeare’s best-known characters, his speech in Act II is among the playwright’s most quoted:

All the world’s a stage,

And all the men and women merely players.

This proclamation, somewhat depressingly, delivers a sudden recognition that human existence is often a performance. We are often reduced to an inauthentic role that we each feel compelled to play.

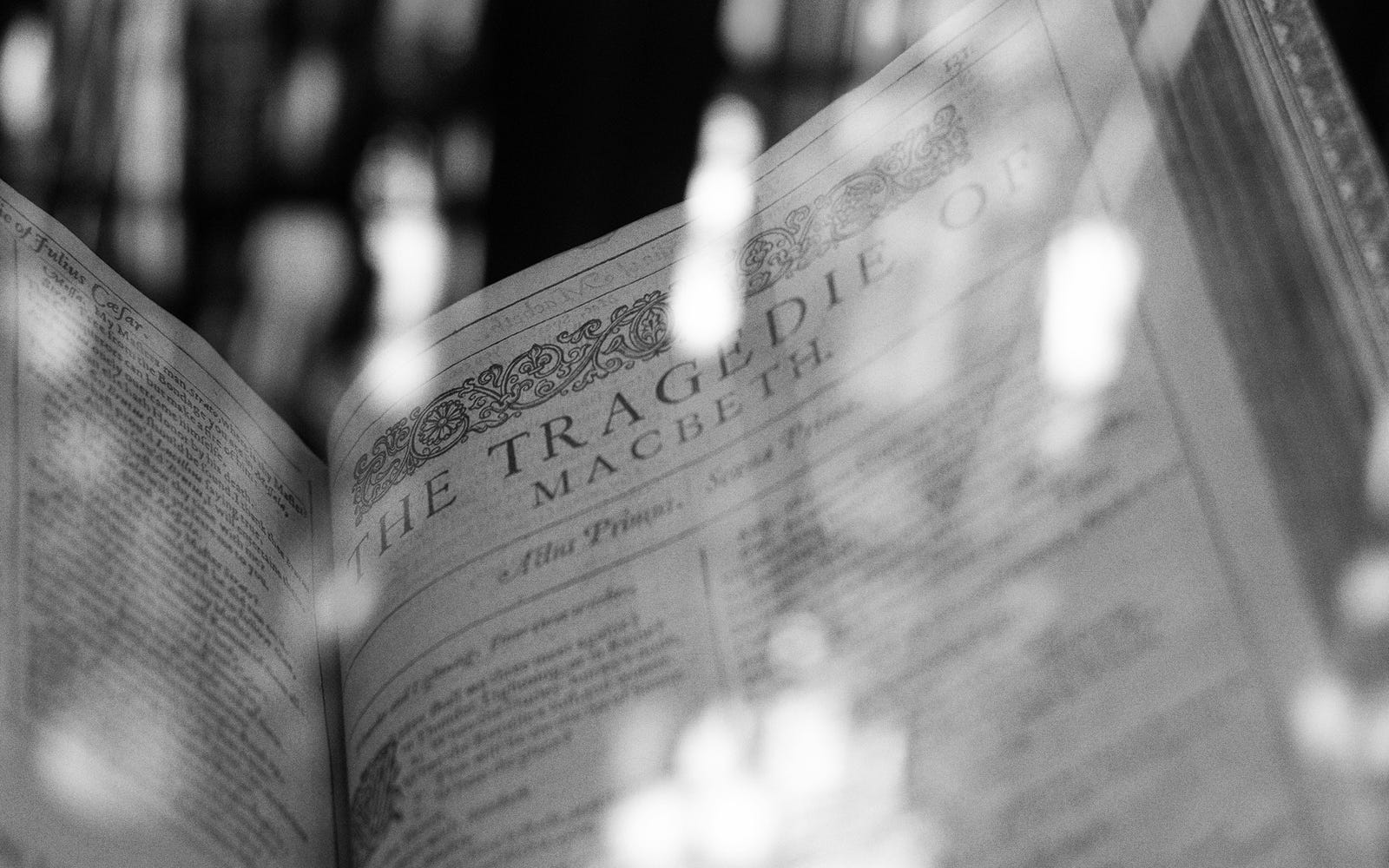

Perhaps like no other playwright, Shakespeare is a master of metaphor, the ways we understand and experience one kind of thing in relation to something altogether different. Many of his metaphors come readily to mind, even without ever having read a single play:

All that glitters is not gold.

Now is the winter of our discontent.

Uneasy lies the head that wears a crown.

Out of the jaws of death.

It is the east, and Juliet is the sun.

But though these metaphors ring familiar, we tend to think of these literary devices as confined to the realm of poetry and literature, with little or nothing to do with common language. However, it has been argued that “metaphor is pervasive in everyday life, not just in language but in thought and action” (Lakoff and Johnson, Metaphors We Live By). That’s to say, rather than being restricted to the world of the Bard, metaphors are actually commonplace in our daily interactions and common expressions.

And that was most certainly true of my smart-alecky childhood, when my beloved but exasperated mother did not hesitate to admonish me when I had gotten too big for my britches.

Everyday metaphors

To develop this idea further, I’ve begun to look a little more carefully at the phenomenon, curious to discover the extent to which metaphors are commonplace in human interaction. According to one system of thought, as already suggested, metaphors are an integral part of our everyday lives. While most recognizably true of language, the claim of the influential book Metaphors We Live By is that this phenomenon also extends to our conceptual systems — the ways we relate to other people and the world around us. If true, that means we not only express ourselves through metaphor, but we think in metaphor as well.

One common example would be how we think about arguments and the metaphor “argument is war.” Quite obviously, “argument” and “war” are very different kinds of things: one refers to verbal discourse and the other concerns armed conflict. Yet it can be difficult to talk about arguments without making use of some kind of metaphor, as exemplified by the following everyday phrases:

I demolished his argument.

She attacked every weak point in my argument.

Your claims are indefensible.

Her criticisms were right on target.

He shot down all of my arguments.

Why does this matter?

If these observations ring true, we not only use metaphors to express ourselves through language, but we also think in metaphors that frame the way we see the world.

And if it’s true that we need propositions to make great arguments — and of course we do — then it also seems true that we need metaphors to express those arguments in ways that are both accessible and persuasive.

Although working out a series of propositions toward a coherent argument has infinite value, there is a suddenness of clarity that metaphors provide. At their best, metaphors offer a kind of epiphany, a moment of unexpected but profound insight.

And that’s why this matters, because as visual storytellers we make use of metaphor — editorially and visually — to challenge our audiences with unanticipated new ways of seeing the world.

Those of us at Journey Group have an opportunity and responsibility to communicate both consciously and conscientiously. By “consciously,” I mean that we need to be aware of how our creative work affects people. And by “conscientiously,” I suggest that our work should have both intentionality and integrity — to aspire to what is good and true and beautiful — for the good of humankind. Knowing how the tools of our creative trade influence people helps us work both consciously and conscientiously.

By way of metaphor, let me suggest that metaphors bring ideas to everyday life.