One sleepy morning, way back in high school, I foggily remember a classmate proposing an elaborate excuse for why her homework was not complete.

During the course of her extended explanation, which was creative if not credible, I mostly dozed. But as our teacher stood in front of the class, she began to perform a small gesture with her forefinger and thumb. Without making a sound, she held up her hand to reveal the mysterious circling of her thumb against her forefinger.

After a few painful moments, our teacher interrupted the moronic bloviation of my classmate and asked, “Does anyone know what this is?” I suddenly lurched awake and thrust my hand into the air. Before I could think I suggested, “Rolling a booger?”

At once our teacher dropped her head and pointed to the door — my silent reprimand to go to the principal’s office.

Later, I was introduced more formally to this obscure visual metaphor — but obviously, a little too late. I learned that moving the thumb in a circular motion over the forefinger can be understood as a gesture symbolizing the world’s smallest record player playing the world’s smallest record, My Heart Bleeds for You.

Although considered by more than one teacher to be something of a smart aleck, I had not yet encountered this mysterious gestural metaphor, which is surprising, since it seems intended to display sarcastic indifference.

This episode from my youth taught me — along with the virtue of thinking before I speak — that visual metaphors are powerful. Whether accessed through physical sight or cognitive imagination, metaphors are essentially images that mysteriously resonate with both suddenness and clarity. But how do they work?

This past summer I explored this question during a workshop at the Basel School of Design in Switzerland — where design titans once roamed the earth. Because metaphors are predominantly understood as the abstract ways we comprehend one kind of thing in relation to something else, they can be difficult to define and classify.

I discovered that it’s much easier to show a metaphor at work than to try to articulate how they work.

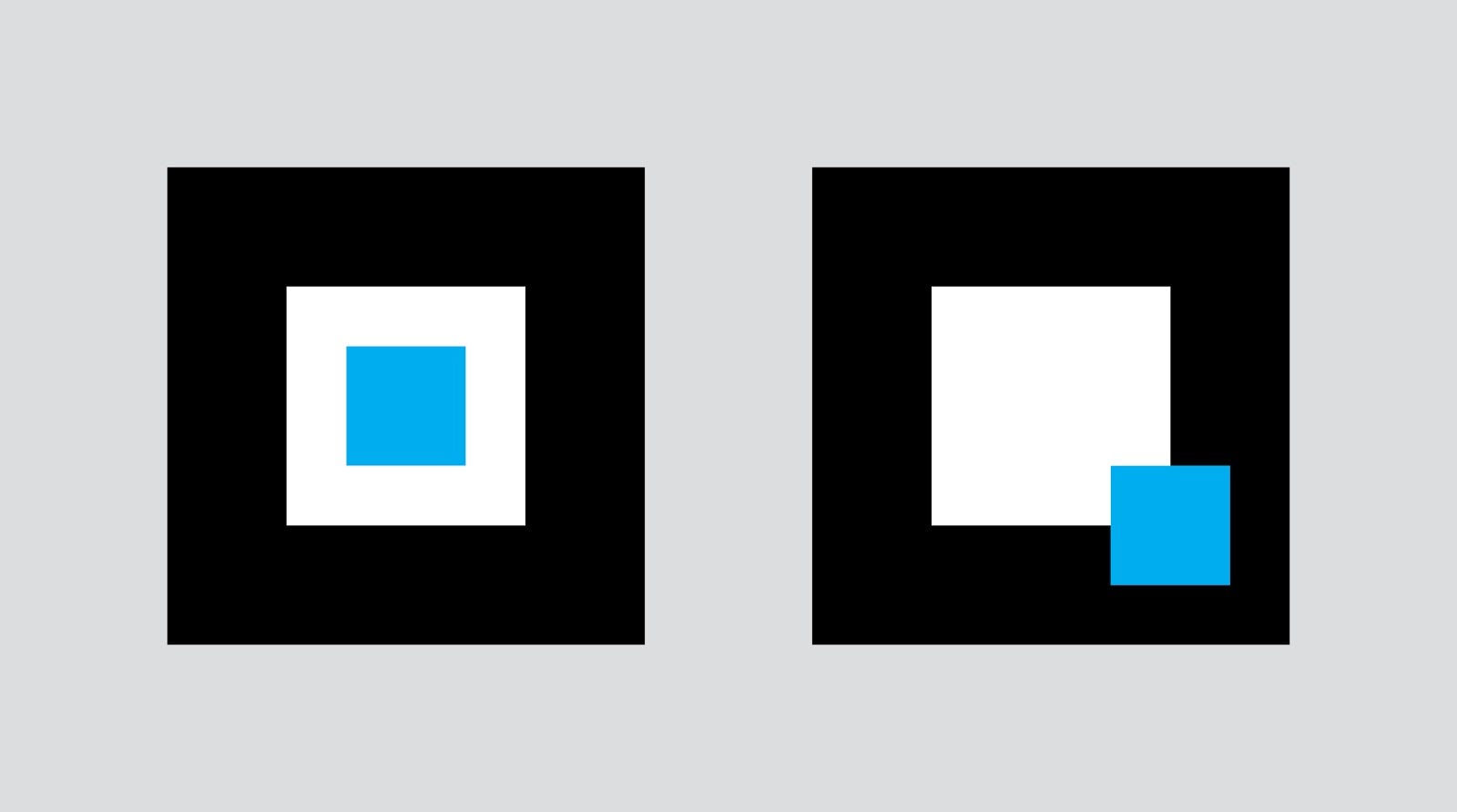

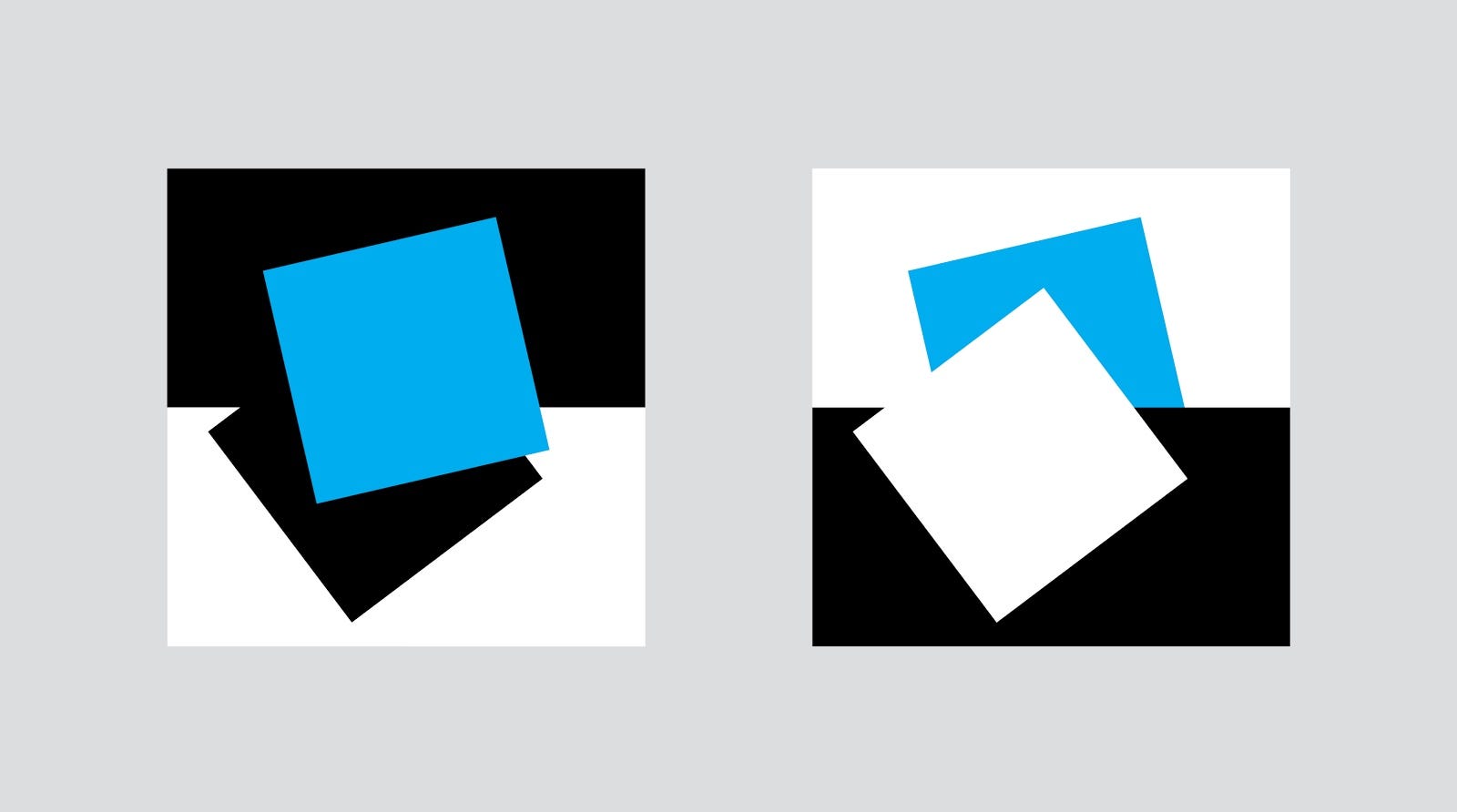

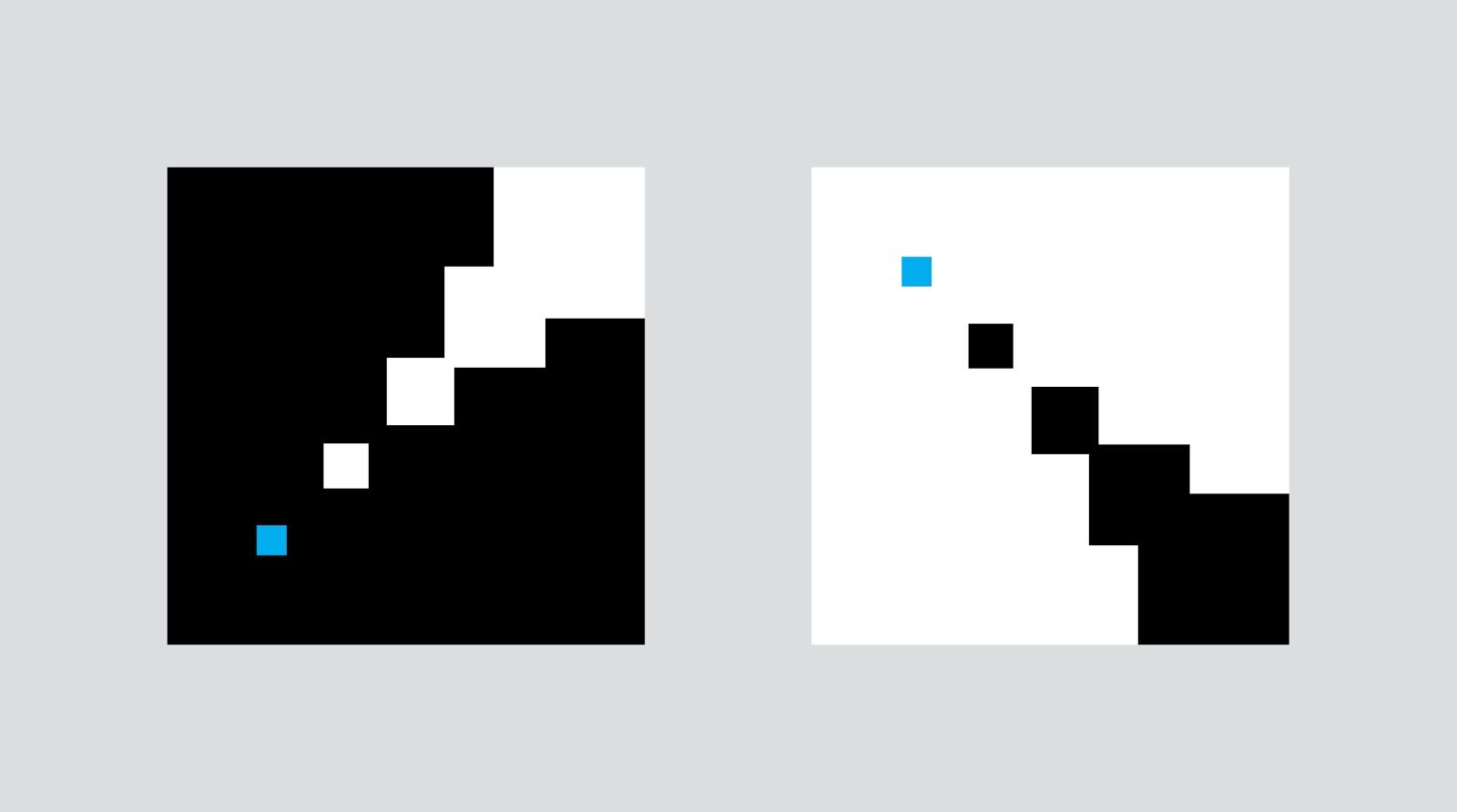

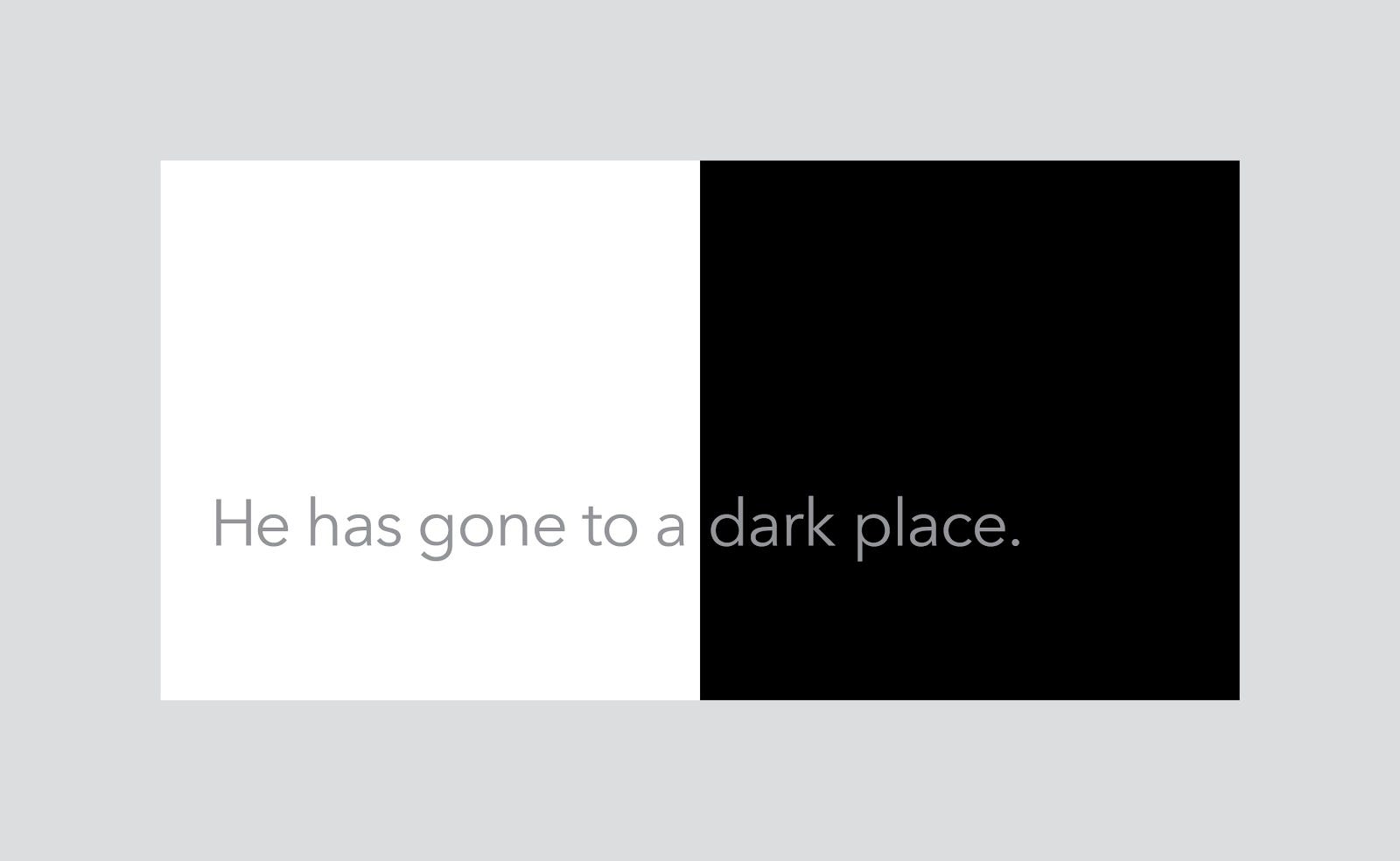

So during our summer workshop, I narrowed my research to orientational metaphors — those that reflect the way our bodies relate to our physical environment and, consequently, provide metaphors with a spatial orientation. By contrasting spatial opposites, such as light versus dark, orientational metaphors also suggest what is positive versus what is negative. That’s why it’s encouraging to say, She has a light in her eyes. But if we say, He has gone to a dark place, we have made reference to a negative state of mind.

It’s worth noting that the Basel School of Design models the forceful idea that design research should be grounded in making images. And so, to explore these ideas visually, I created multiple sets of contrasting images — dozens of them — each set intended to represent some spatial foundation for metaphors. Much to the chagrin of my hapless classmates, I asked them to provide visceral responses to each set of images — to help me learn what kind of reaction could be generated by the simplest of graphic shapes.

Of the many images I created and explored, here are three of them along with their corresponding spatial orientation:

It took my classmates no time at all to identify each paradigm — but to be fair, they were already soaked and pickled in a deluge of images. Nevertheless, these simple squares did not impede their ability to recognize the contrasting spatial relationships as presented to them.

What they unwittingly reinforced, at least in my view, was that metaphors dominate our conceptual thought. Metaphors are images. And we think in metaphor.

By recognizing the spatial foundation for orientational metaphors, it became easier to imagine how they might be implemented with more intentionality. From my earlier comments about the spatial paradigm of light versus dark, the metaphor reflected in the phrase, He has gone to a dark place, could be visually reinforced like this:

That this simple visual metaphor needs no explanation helps make the larger point.

We not only express ourselves with metaphors, but we are awash in them — flooding our thoughts, imagination and experiences.

What’s more, visual metaphors embody those drawn from language, helping reinforce them while bringing them to life, so that a simple black square suddenly becomes a dark place.

Furthermore, metaphors help resolve the disparity between clarity and discovery. While every visual communicator strives for clarity, we know instinctively that we must also invite discovery — engaging our audiences beyond what’s obvious to help stimulate their minds and imaginations. Only then can clarity have its way, to help us persuade and influence.

The Russian filmmaker Andrei Tarkovsky once said, “All art, of course, is intellectual, but for me, all the arts must above all be emotional and act upon the heart.” He goes on to say, “We can express our feelings regarding the world around us either by poetic or by descriptive means. I prefer to express myself metaphorically.”

If Tarkovsky is right, is it too much to say that metaphors are the connective tissue between our cognitive and imaginative lives?

If this is true, then the hundreds of thousands of images we encounter every day — through our eyes but also our imaginations — are influencing and shaping us as humans. Although we’ve developed virtuosic skills at resisting the constant daily barrage of images, we are nevertheless overcome — so that in the end we are ultimately formed by the images we encounter.

Although there is seemingly endless work to be done regarding the impact of these images on humans, it’s nevertheless important to embrace the struggle. We are, after all, exposed to these images daily, and we cannot help but concede that they are shaping us — and in ways that really matter — like the ways we see ourselves and make sense of the world.

The celebrated art director Alan Fletcher once said, “What distinguishes designer sheep from designer goats is the ability to stroke a cliché until it purrs like a metaphor.” And yet we know well that most of the images we see are but clichés and, as such, have little to no power to shape us for the better.

As visual communicators, however, we have a higher calling — to acknowledge the proliferation of metaphors upon our daily lives but also to strive for a more substantive visual discourse.